The Interrupter

Artist and educator Jim Duignan’s practice gets marginalized students involved in their learning.

Jim Duignan Intro Heading link

Everyone has a story to tell—residents of a notorious mental hospital, physically and mentally disabled people, middle-school gang members on the South Side of Chicago. UIC alumnus Jim Duignan BFA ‘91, MFA ’93 is dedicated to collaborating with communities like these to tell their stories through the Stockyard Institute, the name he has given to his 25-year art practice.

It began in summer 1995, Chicago’s hottest on record. Duignan moved his art practice to the Back of the Yards neighborhood on the city’s South Side. Fresh out of grad school, he was there not to teach, but to create an art curriculum for a new school that was being developed to serve students who had dropped out of area schools. Some of the students were not interested in sitting through their classes, but were curious about what Duignan was up to.

“As I was thinking about the curriculum, I wanted to bring in all my artist friends to the neighborhood, so I found some abandoned school on Damen and 48th Streets, and the kids—they were a little more hardcore gang members—hung out with us,” says Duignan, who was testing the curriculum as he was building it. He estimates that 100 artists, including most of his MFA cohort from UIC, visited that summer.

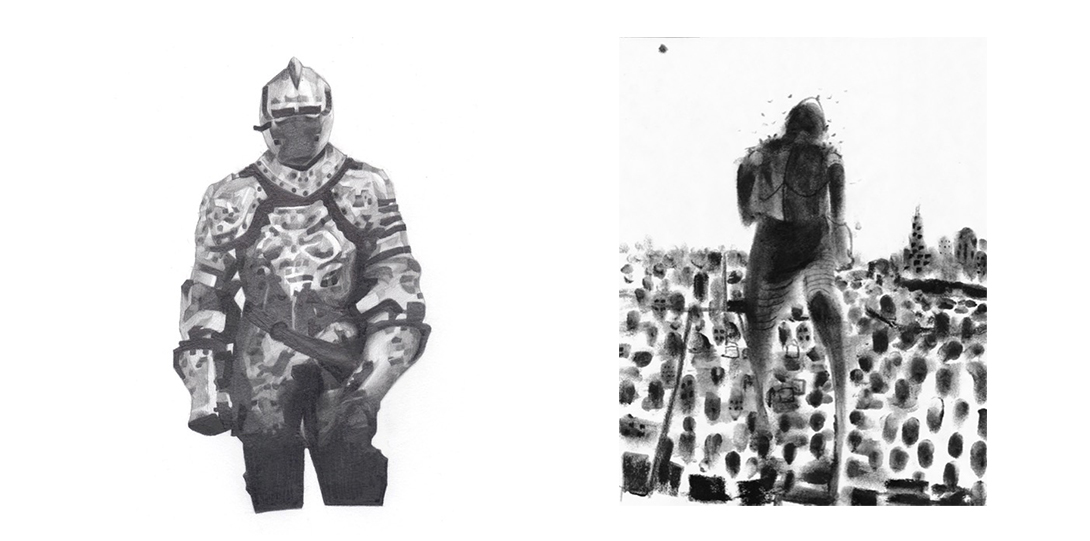

For nearly two months, the students did not make any art—just talked. For maybe the first time in their lives, the students were with safe, thoughtful adults who happened to be artists, poets, performers and musicians. One day, one of the kids said he was afraid of being shot in the back accidentally. When his students opened up like that, Duignan knew it was time to start a project. Together, in the sweltering heat, they began making an artwork called Gang-Proof Suit.

“If you can allow them to build work based on what was most pressing in their lives, someday they’d crack open. They’d keep coming back,” says Duignan.

Active participation in building new knowledge is a hallmark of Duignan’s teaching style and art practice. He was born and raised in Chicago by a police officer father and mother. He found his own elementary and high school education disconnected from his life and interests, but he became fascinated with the teaching methods of the Jane Addams Hull House, where his activist great-grandmother taught. Addams believed that education should be directly related to students’ lives and the betterment of the community in which they live.

Interrupter quote Heading link

“Maybe I was an interrupter. Maybe my art practice is the right interruption at the right time.”

Jim Duignan body Heading link

As a 17-year-old, Duignan first tested this method with a service project for the Boy Scouts. He chose to volunteer with friends at the Cook County Infirmary, known locally as the Dunning Insane Asylum. Duignan says he was curious about the lives of the boys living there. Like many Chicagoans his age, he grew up hearing threats from his parents when he misbehaved that he would be sent to Dunning. He wanted to understand who these boys were and help them tell their stories. He’d spend the 30-minute wait before the Institution’s staff would allow him to enter wondering what there was to hide. But Duignan says he wasn’t there to interrupt or get in anyone’s way. He reacted to his sense of injustice with the quiet, patient activism of showing up, waiting and being there with his students.

“There are a lot of ways you can make something happen. It could be long-term, nonviolent, noninvasive ways of building meaningful relationships. That’s a kind of interruption. I always thought I could wait anybody out, anybody. Maybe I was an interrupter. Maybe my art practice is the right interruption at the right time,” says Duignan.

At the age of 17, Duignan was already making art and attending exhibitions. As he considered college, he knew that he didn’t want to leave the city. After some time at City Colleges of Chicago, he began taking collage classes at UIC with Robert Nickle and sculpture with Martin Puryear. “I had such an incredible introduction to college at UIC. It was home for me,” he says.

Throughout his undergraduate education, he would pause school and teach art to children and adults with physical and mental disabilities, wander the city and do different odd jobs. When he finally completed his BFA, he entered the MFA program, again at UIC. He formed life-long friendships with his peers through late nights making art in each others’ studios and preparing for critiques that would include all of the MFA students, faculty and well-known gallery owners like Rhona Hoffman and Donald Young.

I'm not here to teach you anything quote Heading link

“I’m not here to teach you anything. I’m here to let you share what you’re about.”

Jim Duignan Body Heading link

“I think about UIC all the time. It was a really important time in my life in terms of thinking of myself as an artist. I draw on that more often than I think,” he says.

And lately, Duignan has spent a lot of time thinking about the trajectory of his career as he prepares for “Stockyard Institute: 25 Years of Art and Radical Pedagogy,” a major museum retrospective of his work curated by Julie Rodrigues Widholm that kicks off at Chicago’s DePaul Art Museum in March 2021 before traveling to other cities. The show comes on the heels of receiving an endowed Chair and professorship from DePaul University, where he is an associate professor of visual arts and secondary education and chair of visual art education.

As an artist, Duignan has spent the past 25 years practicing the radical teaching method of listening to people who are not used to having their voices heard. “I’m not here to teach you anything. I’m here to let you share what you’re about,” he says. Ultimately, his students learn to value their own voice.