Connecting with Indigenous Communities

Alumna brings Native American Communities and UIC researchers together to raise visibility of Chicago's Indigenous residents.

Intro Heading link

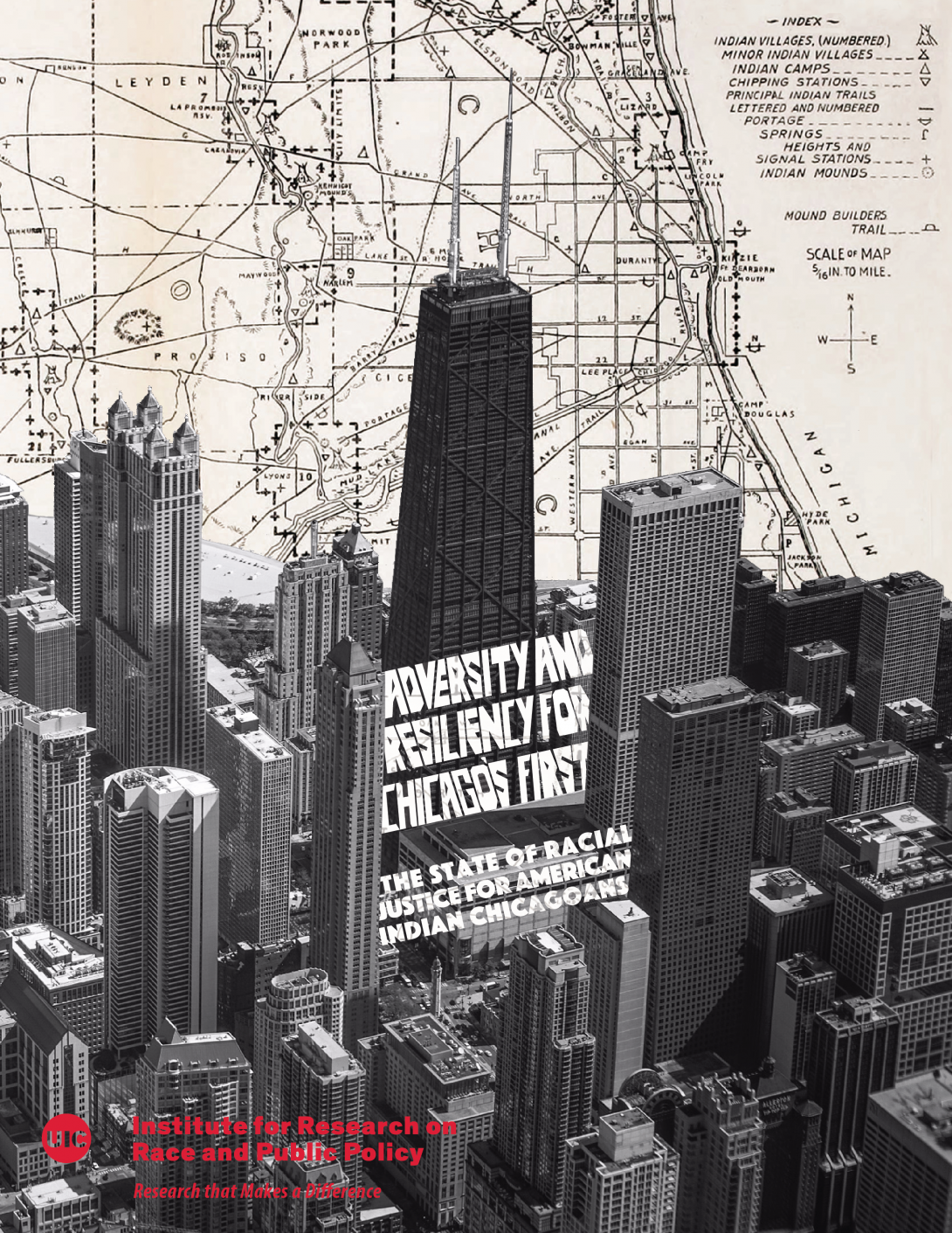

Cynthia Soto BA ’97, MEd ’05 wants you to think about Native Americans—the engineers, lawyers, artists, teachers, students, neighbors and colleagues who live and work throughout Chicago, along with the historical tribes on whose land the city now sits. To raise their visibility, Soto, who is Sicangu Lakota and Puerto Rican, recently brought Native American community members to the table with research staff at UIC’s Institute for Research on Race and Public Policy (IRRPP) to author Adversity and Resiliency for Chicago’s First: The State of Racial Justice for American Indian Chicagoans.

“I feel like what is really powerful about this report is that all the community organizations were partners. Most research doesn’t do that for us,” says Soto.

As Chicago’s only public research university and one of the most diverse universities in the United States, UIC was a natural fit for partnering with the city’s Native American communities. The report was funded by the Spencer Foundation, released in June 2019 and includes quantitative and qualitative data on population, housing, education, economics, health and justice for Native Americans populations living in Chicago. Each section includes an essay by a Native American researcher. Soto, who worked in Chicago Public Schools for many years and is currently director of the Native American Support Program at UIC, wrote about education.

pull quote Heading link

“I feel like what is really powerful about this report is that all the community organizations were partners. Most research doesn’t do that for us,” —Cynthia Soto

Part 2 Heading link

While the report uncovered disparities in housing, income, health and incarceration for Native Americans, it also acknowledged the communities’ organization, activism and resiliency. For instance, Chicago is home to the American Indian Center (AIC), one of the oldest urban-based Native community centers in the United States. For decades, it has served as a place where the city’s Native American population, one of the largest in the country, could come together. The AIC became a partner with the IRRPP on the report as part of its commitment to engaging with universities to meet the needs of its community, one of which is data.

Researcher Angela Walden, who is a member of the Cherokee Nation and clinical assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry and research assistant professor in the Department of Medicine at UIC, says she has had trouble in the past finding data for Chicago’s Native American populations when applying for grants. Often, Native Americans are grouped under “other” on forms, rendering them nearly invisible in the data. “I think the IRRPP report is critical because it fills a gap that I need to make the best case to funders for why services are necessary,” she says.

Walden wrote an essay on health and images of Native Americans in mainstream spaces for the report. In it, she describes a walk down Michigan Avenue in Chicago, taking readers past the historical depictions of Native Americans as noble savages in public sculptures and the logo in the Blackhawks’ store that she encountered. She says it made her think about how these images shape reactions to contemporary Native Americans in Chicago. “I wanted the reader to understand that it’s not just about big picture things. It’s about our relationships with one another and the day-to-day reactions that people have when they meet a Native person,” she says.

Cynthia Soto echoes that thought when she talks about visibility and how it can feel like it only exists during Native American Heritage Month. It’s important, she says, for people to “educate themselves about the history and be aware of how that history has played out. And then also ask ‘What are some strengths and powerful initiatives that are currently happening in Native communities?’”

Now that she has Adversity and Resiliency for Chicago’s First, Soto is using her community connections to raise visibility year round. The report has been shared with the Field Museum to help inform the work it is already doing to reconsider its Native American exhibit, which will be the museum’s first large-scale exhibition curated by a Native American scholar in collaboration with their community. It also was circulated at the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s housing fair. And Soto will take it to an event hosted by the Spencer Foundation and the Field Foundation to put it in front of organizations that can help meet the needs laid out in the report by funding programs.

Building on the work of those who came before, the report’s authors and advocates continue to raise their voices and strive for a more equitable future that includes the voices of America’s indigenous people. “Representation really does matter,” says Walden.

CTA Heading link

Read more about this and other reports from the IRRPP in UIC Magazine.