Call to Action

UIC and UI Health are providing critical leadership in the midst of a crisis—and their efforts may help create a better future.

By Cindy Kuzma

copy Heading link

During the earliest days of the COVID-19 pandemic, the phrase “we’re all in this together” dominated the cultural conversation. But faculty and staff at UIC and UI Health knew the sentiment was oversimplified. Because of UIC’s longtime commitment to serve the underserved, they understood that the disease would likely disproportionately affect communities of color, the poor and all the city’s most vulnerable populations.

Data soon illuminated the disparities. A May report from the Chicago Urban League’s Research and Policy Center found that while Black residents make up 30% of the city’s population, they represented 60% of COVID-19 deaths. As of mid-November, the infection rate among Latinx residents was about 6%, more than two and-a-half times that of white Chicagoans. And a Bloomberg CityLab analysis found the same neighborhoods struggling with poverty and pollution, including predominantly Black areas on the South and West Sides, were also hit hardest by the virus.

UIC and UI Health clinicians, researchers and policy experts didn’t wait for the numbers—they swiftly leapt into action to lead COVID-19 response and relief efforts. From advising public health departments to shoring up supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE) to pioneering new testing, treatment and contact tracing methods, these projects aim to mitigate the current outbreak—and to repair broken systems and better serve all citizens for years to come.

Caring for the Whole Community Heading link

Few populations have been more severely affected by COVID-19 than those experiencing homelessness. In March and April, about one-fourth of people staying in shelters were COVID-19- positive, according to Dr. Evelyn Figueroa, UIC professor of clinical family medicine, family medicine residency program director and community activist.

Dr. Stockton Mayer also works regularly with people experiencing homelessness at a needle exchange and HIV testing site on the West Side, part of the School of Public Health’s Community Outreach Intervention Project. As the pandemic’s impact rose in March, Mayer—assistant professor of clinical medicine in the College of Medicine—began asking questions. Where should people isolate if they don’t have a home? And how could they access testing and medical care?

He approached the city for guidance, and public health officials responded by connecting a group of health care providers seeking the same information. Several institutions—including UI Health, Rush University Medical Center and Lawndale Christian Health Center—formed a group called the Unsheltered Chicago Coalition.

The coalition transformed Hotel One Sixty-Six, an upscale Gold Coast property, into what was called a “shield center.” People who had no place to quarantine or isolate received a room, food and medical care. Mayer and other medical professionals would go out to the shelters and other sites where individuals had been exposed to provide further testing.

At first, UI Health and UIC assisted on a volunteer basis. In June, the city officially contracted the group to provide testing for the shelter system, long-term care facilities and other places where people live in groups. That’s when UIC Nursing Assistant Professor Rebecca Singer joined the effort. She harnessed her experience in humanitarian relief to begin leading a group of volunteers and employees, including many UIC students in the Colleges of Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy and Dentistry.

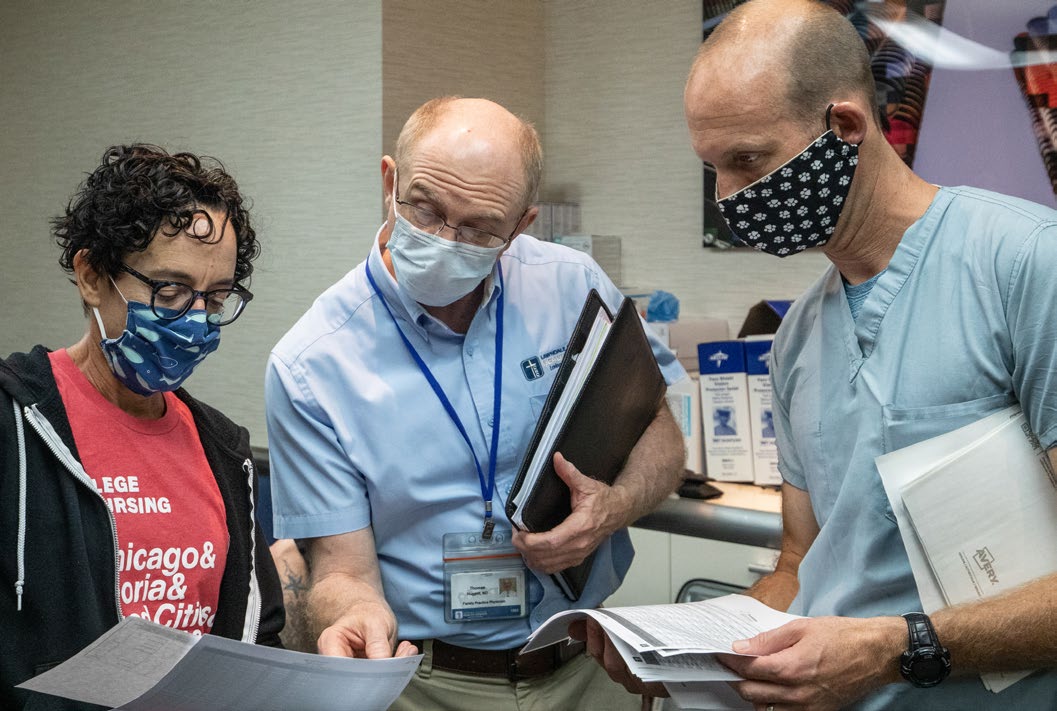

Most days of the week, they travel with testing equipment to a site deemed high priority by the city—usually a shelter or long-term care facility, or perhaps a jail, behavioral health center or similar setting. Once they arrive, in full protective gear, they must overcome significant barriers.

“These are people with a deep distrust of the health system, and for very good reason. Our systems haven’t served them,” Singer says. The team works to make connections and allow autonomy, offering people choices about whether to be tested and how much data to divulge. “We try to engage on a personal level to convince them we are trying to help their community, not hurt their community.” By mid- October, the group had performed more than 10,000 tests and had a contract to continue through the end of 2020.

While all this was happening, the outbreak was intensifying at Pacific Garden Mission (PGM), which has the capacity for 950 people. At one point, 70% of those in the building were COVID-19-positive.

Figueroa stepped in at the end of March to form the PGM Emergency COVID Medical Response Team. She began by insisting on masking, handwashing, surface sanitizing and other basic infection control measures, simple steps which nonetheless required significant behavior shifts. She took great pains to protect her team, creating a “wall of PPE” where each person could hang their own equipment. “People knew I was going to fix their mask if they got near me,” she says.

She also oversaw the setup of four COVID-19 isolation units. In addition to people from the mission who tested positive, these facilities were also able to accept others with nowhere to go after they were released from the hospital. Eventually, they’d care for more than 200 people with COVID-19.

During those intense weeks, Figueroa was struck by how many other basic services were interrupted, including housing support, funds for medication and access to food. “It was disempowering to a community that already is so invisible, and it was hard not be able to help more,” she says. But it only intensified her commitment to focus on the social determinants of health in her medical practice, as well as her devotion to the Figueroa Wu Family Foundation, which operates a food pantry in Pilsen. “It’s all showed me this is where I’m supposed to be, the work I’m supposed to be doing,” she says.

Around the city, many other UIC-related efforts arose to fill Chicagoans’ unmet needs. Pregnant women face significant risk from the disease, but wearing masks when they’re at the hospital for delivery protects them. Masks for Moms—a partnership between the UIC Center for Excellence in Maternal and Child Health, Black Girls Break Bread and other community organizations—collects and distributes homemade masks to moms-to-be.

UI Health’s Mile Square Health Center—a network of federally funded community-based clinics—not only provides COVID-19 testing and medical care, but has also taken steps to support its communities in other ways. Connections with Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Illinois, Jewel-Osco and Mariano’s have yielded food boxes for COVID-19 positive Medicaid patients and their families. Other partners, including University of Illinois Cancer Center and the Residential Association of Greater Englewood, have assembled community kits packed with masks, hand sanitizer and educational materials. Through these efforts, thousands of boxes of food and supplies have reached residents in need.

Advancing Prevention and Treatment Heading link

Other faculty and staff have stayed busy in the labs and clinics, studying the biological basis of the disease and various prevention methods and treatments in hopes of bringing the disease under control. Among the most urgent needs was a vaccine against COVID-19. Investigators at UIC had long been involved with vaccine trials, including those for HIV, a disease Dr. Richard Novak has spent most of his career studying and treating.

“When this particular pandemic broke, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) came to us because they knew we already had the infrastructure and experience to do this kind of work,” says Novak, professor and head of infectious diseases at the College of Medicine.

In August, UIC began a phase 3 clinical trial of a vaccine developed by the biotech company Moderna. The vaccine uses RNA, a molecule related to DNA, which instructs the body to produce antibodies against COVID-19. Then, people who are exposed to the disease can mount a defense against it, without getting sick.

The trial, led by Novak, confirmed how well the vaccine works. Participants received either the vaccine or a placebo and reported back every week on whether they’ve developed symptoms. If they do, they’ll receive a COVID-19 test; their blood will also be checked regularly for antibodies. They’ll be followed for two years, though the results are already known, due to the surge in COVID-19 this fall. The vaccine was shown to be 94.1% effective in preventing COVID-19 disease, and was given emergency use authorization from the FDA on December 18.

About 75% of the participants from UIC were people of color, who are both disproportionately likely to be infected with COVID-19 and to experience worse outcomes. “We needed to know if these approaches are going to work in people of color,” Novak says. “And if Black and brown people did not participate in these studies, we wouldn’t know for sure.”

Bonnie Blue Quote Heading link

It’s a privilege to be able to participate in something that may help humankind to survive.

second portion of advancing treatment Heading link

This imperative compelled 68-year-old Chicagoan Bonnie Blue to sign up. Initially, she wanted no part. She was well aware of historic incidents of mistreatment by the medical community toward Black people, including the Tuskegee Study, in which Black patients went untreated for syphilis. Plus, she’d heard too many recent stories of disparities in treatment among her friends and family.

Yet she kept a close eye on the pandemic’s progression, especially in communities of color. “I could not separate those rising numbers from mom, dad, uncle, sister,” she says. “These are individuals, human beings, not statistics.” The image of the first woman who died in Chicago lingered in her mind, as did the stories of babies born to infected mothers.

When her grandson told her he was expecting a child, she felt compelled to act. She researched her options, filled out a survey through the NIH, and soon received a call from UIC. On Aug. 24, she became the first person to receive an injection. “I don’t look at it as an obligation—it’s a privilege to be able to participate in something that may help humankind to survive,” she says.

The vaccine trial was then one of seven clinical trials offered at UIC—among more than 50 COVID-19-related research studies using human subject volunteers, according to Dr. Joanna Groden, UIC vice chancellor for research.

Novak is also overseeing trials of the antiviral drug remdesivir, both on its own and in combination with an immune-modulating medicine called baricitnib, as well as in combination with interferon beta. He is the principal investigator of a new phase three clinical trial of a COVID-19 vaccine candidate developed by Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson. And, he’s senior investigator on a study helping the company Regeneron Pharmaceuticals test preventive therapies called monoclonal antibodies, on which Dr. Jesica Herrick, associate professor of infectious diseases in the College of Medicine, is principal investigator.

“Instead of giving a vaccine which induces your body to make antibodies, these treatments infuse antibodies directly,” Novak says. “We call this passive immunization as opposed to active immunization, and we have good reason to believe it works, especially for mild to moderate disease.”

University investigators are also testing options for more serious cases. Dr. Jerry Krishnan, professor of medicine, is leading a study in hospitalized patients of a drug called sarilumab, previously approved to treat rheumatoid arthritis. This therapy targets cytokines, small proteins produced during the immune response to COVID-19, and may reduce the risk of more severe complications and death.

Krishnan is also working to better understand the progression of the disease, leading the UIC arm of a project called Predictors of Severe COVID-19 Outcomes, or PRESCO. And, he’s co-leading a series of three clinical trials called ACTIV-4, to study how blood thinners could reduce clotting, a common complication in people with COVID-19. Other researchers are studying the experiences of health care providers treating COVID patients, as well as the use of convalescent plasma as a therapy.

As of early December 2020, UIC investigators have received more than 100 externally sponsored research awards for COVID-19-related studies, Groden says—totaling approximately $32 million. Some of these COVID-19-related projects contributed to a record-breaking total of $410 million in research funding for fiscal year 2020, which ended on June 30. The first quarter of fiscal year 2021, which includes July to September, UIC COVID-19-related research funding totaled $24 million. Groden’s office, too, has gone into overdrive, ensuring that all research processes move smoothly, and that labs and clinical investigators have what they need to succeed.

“Our office works hand in hand with faculty and other researchers to promote their ability to ask important questions and compete for funding to support their research programs,” she says. Even research not directly related to COVID-19—for instance, studies on better visualizing data or developing education technologies for special needs students—will benefit populations affected by the pandemic. “These big discoveries will change people’s lives.”

Containing the Cases—and Shaping the Conversation Heading link

The university’s College of Medicine’s Division of Infectious Diseases and School of Public Health have long led the nation in educating the next generation of professionals while caring for both the campus and the surrounding community. So when a public health crisis erupted, officials quickly put their experience to good use.

“UIC and UI Health were early in implementing universal masking and mandating face coverings in March,” says Dr. Susan Bleasdale, acting chief quality officer and medical director of infection prevention and antimicrobial stewardship. “And we continued to be at the forefront in planning return-to-campus measures.” The health system and health science colleges remained safely open throughout the pandemic, and campus leaders recognized a well-designed response plan was needed for the rest of the campus to return.

Through the late spring and summer, a multidisciplinary expert group including Bleasdale and Professor of Epidemiology Dr. Ronald Hershow participated in a series of intense meetings about how to ensure a safe learning environment for students and staff. In these sessions, they crafted a surveillance testing strategy using saliva tests that delivered results within hours. A separate team of infectious disease and environmental health and safety experts reviewed all campus spaces to ensure physical distancing and adequate air handling.

part two of previous Heading link

“The idea of this program was not to test people who were having symptoms of COVID; it was to generally test the campus population for COVID,” Hershow says, providing an early warning about cases on campus and a chance to stop them from spreading.

Beginning in mid-August, saliva testing became available to high-risk student groups, including athletes, those in the performing arts and dormitory residents. Students who test positive are notified within 24 to 48 hours and given support to isolate and seek treatment if needed. As capacity has increased, testing has become available for others on campus and ultimately will be part of a regular screening program for on-campus students and staff.

“Anytime you have a rapid test, it has to be tied to rapid action,” Bleasdale says. “That’s why it makes sense to tie surveillance testing with a contact tracing team.” Contact tracing involves determining who an infected person may have exposed during the time when they were contagious—for instance, roommates, classmates or teammates. Those people must then be notified and instructed on quarantining and testing.

Many universities have relied on their local health departments for contact tracing. But UIC took a different path and built its own system for students based off its employee health contact tracing program for staff. Hershow hired two alumni who completed their master’s degrees in epidemiology in 2019 to head up the UIC COVID-19 Contact Tracing and Epidemiology Program (CCTEP): Ellen Stein MS ‘19, who’s now the program’s director, and Jocelyn Vaughn MS ‘19, research data scientist.

In about two months, they built the program from the ground up, hiring around 20 contact tracers to start. Most were graduate students in public health. “They know the campus; they know the high-traffic areas; they understand the particular stresses of being students,” Hershow says. “While you’re following the contact, you’re calling them every day asking them if they’ve developed symptoms. We’ve had our contact tracers also ask about things like what they watched on Netflix the night before.” That’s not because they’re tracking entertainment trends—rather, they’re building connections so students feel comfortable sharing information, which is then treated with strict confidence.

Stein says connection is crucial in the success of a delicate task like contact tracing: “We’ve seen that rapport factor borne out and be essential in our ability to conduct thorough investigations and gain the trust of the people we’re interviewing,” she says. In fact, they’ve had about a 93% success rate in reaching people with COVID-19.“We can then get accurate information about who may have been exposed to them and take the appropriate public health steps.”

The students working as contact tracers are also planning research using the data; eventually, knowledge gained from the program could help public health experts everywhere in their efforts to contain COVID-19, Stein says.

Of course, UIC experts are already sharing their knowledge and resources with the greater community, including advising those making critical public health decisions. In April, a group of 27 scholars across the university system—including Dr. Lisa Powell, distinguished professor and division director of health policy and administration—prepared a policy report detailing the pandemic’s impact on Illinois finances.

The College of Medicine has an intergovernmental agreement with the Illinois Department of Public Health (IDPH) to provide support and assistance during the COVID-19 response. Bleasdale leads a team that includes infectious disease and infection prevention experts from the Division of Infectious Diseases and epidemiologists from the School of Public Health.

Early on in the outbreak, a UIC team including Dr. Mahesh Patel and Dr. Scott Borgetti provided on-site investigations of the first outbreaks at long-term care facilities within Illinois. The UIC infectious disease team has provided ongoing outbreak support for long-term care, Department of Corrections, day care centers and other congregate settings. The team has provided mitigation guidance, testing strategies for containment and reopening guidance throughout the pandemic.

Christina Welter, clinical assistant professor of health policy and administration, worked with IDPH on an incident command system to organize and prioritize planning; meanwhile, Steven Seweryn, clinical assistant professor in the epidemiology and biostatistics division, helped build a plan for synthesizing and communicating vast amounts of data.

And it continues with on-the-ground efforts. The School of Public Health co-leads a $56 million city-funded contact tracing program, which will focus on communities most impacted by the pandemic. And with a grant from AbbVie, the Community Outreach Intervention Projects—the same HIV/AIDS prevention effort Mayer works with— has also hired staff members to serve as COVID-19 ambassadors in neighborhoods like Auburn Gresham and Little Village. They distribute masks, promote social distancing and help connect people to essential health resources if they do become sick.

The College of Medicine and UI Health also have a contact tracing program with the Chicago Department of Health to expand their capacity and allow for more rapid contact tracing. “It makes sense that these are our patients whom we can quickly notify and identify contacts to guide on quarantine and testing to slow the spread of COVID-19,” Bleasdale says.

Nurturing Hope for the Future Heading link

Whether they’re working directly with patients, overseeing contact tracing or research funding from their home offices or conducting clinical trials, UIC faculty and staff admit these efforts haven’t been easy. Many have added COVID-19 responsibilities to their existing workloads. Figueroa says she often cried on her way to and from the shelter; Bleasdale wishes for added hours in the day to juggle all her duties.

Though the work is often grueling, it’s also intellectually engaging, providing those in infectious disease, public health and adjacent fields an opportunity to serve their highest purpose. “This epidemic reminds me every day of why I chose to go into infectious disease epidemiology,” Hershow says.

Interdisciplinary and inter-institutional teams—rare in health care—have joined forces, breaking down silos once hindering progress. “We say that these problems are intractable; we can’t possibly house homeless people or provide good care,” Singer says. “If there’s a silver lining of COVID, it’s that we’ve shown we can change for the better.”

Plus, many students have signed on as contact tracers, testing administrators, and in other roles, inspiring a broader hope for the future. “They’re all stepping up and trying to make a difference,” Singer says. “As an educational institution with a mission to achieve equity and serve a diverse student body, we are teaching our students: ‘This is what you do; this is how you serve.’”